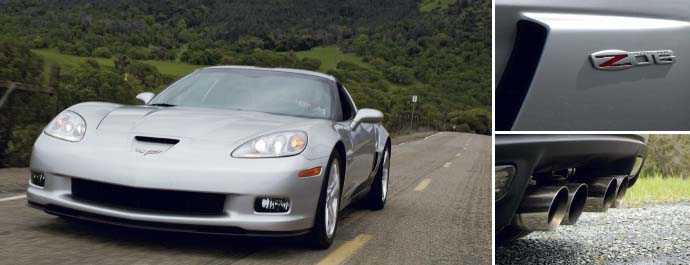

Taking the First Shot

With the cracking of GM's computer code, the first generation of C6 Z06 tunercars has at last hit the road. Jeff Glenn cops a drive in Synergy Motorsports' cammed-up prototype to see if even more power means even more speed, or even less rear-tire life.

Photos by Jay.

Marsh Creek Road is a long, twisting two-lane that used to cut a forgotten path through mile upon mile of scrub orchards and riverbank pasture. Sports-car nuts desperate to flee Bay Area congestion would slog their way out through gritty suburban Concord, stomp the gas for a few minutes before reaching a little cow outpost called Clayton, and then scream down Marsh Creek's wide-open straights, sinewy hill crossings, and flat-out sweepers; miles and miles later, the road would finally bend east in a 90-mph sweeper and deposit them down in the broad Central Valley.

Concrete contractor Jeff Huston—a big, red-headed, slow-talking guy with the friendly but gimlet eye of a person who's made his own money—lives in Clayton, not far from Marsh Creek Road. He knows how it used to be. He also knows, from living in the suburbs that have long since absorbed the old orchards and pastures, that it's no longer the road we all used to think was our own secret raceway. The old two-lane has become straightened and widened and well traveled and patrolled—certainly no place to hit 150+ in fourth with the engine still pulling. But the fact that the new Z06 can land you in jail perfectly well right off the showroom floor is immaterial to people like Huston. He's one of those guys whose interest in power is not to ask "how much," but rather to ask "how much more?"

From the moment it was announced, tuners who cater to mindsets like that all agreed that the LS7-powered Z06 was the new target du jour. Just two issues ago, in CM24, we talked to a handful of these players and asked how much more power could really be found inside GM's 427-inch smallblock. Their consensus was clear: The powerplant could certainly be improved—everything can—but it wouldn't be easy and no no one would get far until programmers cracked the computer.

The hackers finally got in there a month or so after we went press, and the world is starting to see the results. Dying to take the first shot at one these ramped-up supercars, our chance came to pass when Synergy Motorsports let us know they had something we might want to see: The first road-legal Z06 tunercar offered for full-throttle testing. Jeff Huston had been the project's backer.

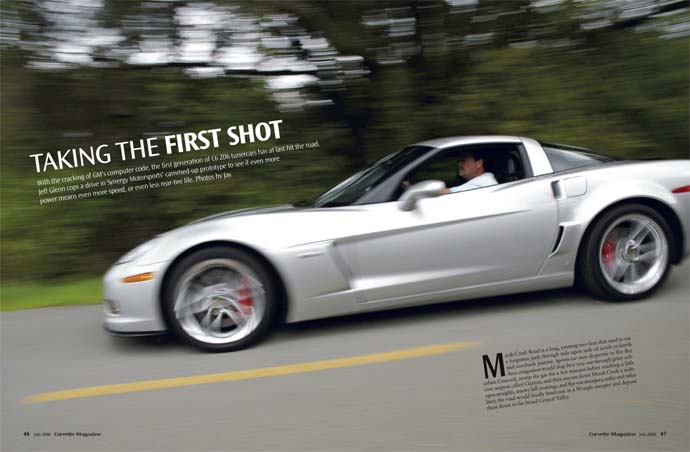

For our first drive, Rick Hollenback at Synergy put us into Huston's working prototype, a car built to what Synergy calls its Stage One level. This fairly restrained package is limited to tuned high-flow headers, a proprietary cam ground to Hollenback's specs, and key Powertrain Control Module (PCM) alterations to take some of the fat out of GM's original, warranty-minded fuel/air and ignition curves.

With Stage One, Synergy's goal was simply to make the LS7 come alive quicker and harder at mid- and full-throttle without losing the tractability that makes it so pleasant everywhere else. "There's definitely a group that likes the conservative power, the smogability, and the stealthiness" of a milder approach, Hollenback says. Based on past LS1 and LS2 experience and armed with the company's hydraulic Dynapack dyno, he set out to develop a tuned Z06 with all of the stock model's friendly demeanor and a new streak of fury when stepped on.

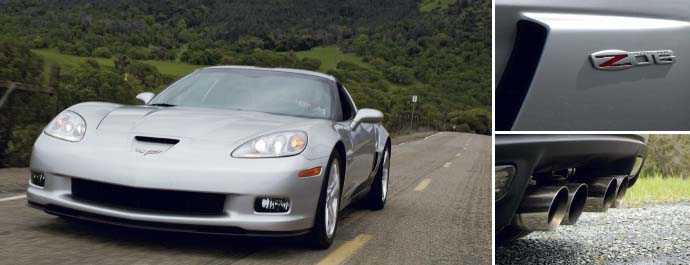

Synergy's best runs on a dead-stock Z06 produced 479 rear-wheel horsepower (RWHP) and 462 lbs-ft of torque; no shabby baseline. Based on earlier studies made of the LS7's factory cylinder heads and exhaust tract, Hollenback then bolted on a set of tuned headers manufactured by Kooks in New York, raising the otherwise unchanged powertrain to 493 RWHP and 479 lbs-ft torque.

Meanwhile, Synergy and others had been poking around in the car's PCM to figure out how the original programming was structured and, therefore, where extra power might still be extracted. "You'd be surprised at how well [tuned] it was from the factory. We really had to work for it," Hollenback recalls. The timing table really surprised me...I was [only] able to smooth out the graph [a little] with better transitions, adding a couple of degrees here, backing it down a bit there." More notable gains were found by restructuring the very conservative factory air/fuel profile, which kept the car fairly rich under high load or high rpm. (That isn't unusual for a factory program; in case there's a hardware or software glitch, the warranty holder wants a big cushion before the engine goes so lean it holes a piston.) "It woke up after playing around with the mixture. Without looking at the camshaft or playing with the air/fuel, there just wouldn't be a lot more power to find."

Hollenback also fiddled with GM's stock cam profiles, which he felt were quite good to begin with but perhaps a tad undercooked. "I do see myself as more conservative than most tuners; more down to earth. [With cams], I'm not looking to make numbers for some internet-forum chat."

Before beginning physical testing of grinds on the dyno, Synergy secured a brand-new LS7 cam from the factory and reverse-engineered GM's thinking. Then, by combining that knowledge with flow-bench data taken on a factory head with and without the stock intake manifold, Hollenback determined the stock setup was "...light on the intake and heavy on the exhaust," a clever trick to add a little extra duration in aid of the EPA test cycle. Also, while the exhaust lobes looked like a good match for the heads' airflow, the intakes were still on the safe side—more like a regular factory grind than the radical, tuner-type shape of the exhausts.

"We said 'Okay, let's deal with one thing at a time and see where this motor really does change.' For starters, we took the original profiles, added a little more intake, and almost copied the exhaust." Eventually, Hollenback got the profiles dialed in using numbers that weren't too far off his first estimates. "When you're looking at the dyno, if you add intake duration or make it breathe a bit better and then you only see a horsepower rise up at the top, there was never really any restriction in the intake tract. Conversely, when we [began gaining] power almost across the board, we knew we were going in the right direction. [We ended up shifting the intake] about ten to 12 degrees and moving the lobe center from 120 to 118 degrees." Hollenback learned that increasing the lobe-separation angle (or LSA, referring to the distance between intake- and exhaust-lobe centerlines) would bring a little more torque delivery in the middle even while the longer intake duration raised max power up at the top. "Whenever you close the door on the intake a bit later, you're going to bring a bit of top-end back. At the same time, you're also allowing a little more air into the cylinder, which is going to fill it a bit better." The result was a cam that gave small gains in peak output but raised midrange punch; more importantly, the new grind also prepared the engine to take advantage of the PCM changes Synergy was planning to add next.

With the new cam and headers, the dyno showed 502 RWHP and 476 lbs-ft of torque. Finally, when Hollenback put in his new PCM tuning, it all came together with a rise to 525 RWHP, 494 lbs-ft of torque, and stronger delivery right through the midrange on up. "The new mixture keeps the motor from being quite so rich, so it's able to accelerate a lot faster."

Dyno improvements are one thing, but the real test of a tuneup occurs in the engine compartment. That fact brought us out to Marsh Creek Road and the private garage of Jeff Huston.

Unlike most of Hollenback's clients, Huston is new to the Corvette world. He ditched a Porsche Carrera for this car, and is surprised to say that he loves it in a way that he never expected to love a Corvette. (How many other C6 owners use a VW Phaeton as their family car and have Ducati stickers on the back of their work truck?) Huston wasn't out to create a stoplight killer or a track-only playcar; he was simply interested, both viscerally and intellectually, in finding out how good the Z06 could get without losing its grip on the everyday world. After a contact at the Chevy dealer introduced him to Synergy Motorsports, Huston had his car on Rick Hollenback's dyno as soon as it got past the break-in miles.

What was eventually accomplished? In normal traffic, the Stage One mill behaves just like a stock LS7. "If you go easy on it, it even gets great mileage," Jeff offered. But the real question of this test is effectiveness, not economy: Specifically, can the new Z06 really use any additional power, or will every increase past the stock level simply kick in the traction control that much sooner?

Well, Lord Acton would be pleased: It may indeed still corrupt, but in the Z06's case power does just not evaporate into smoke and ASR warning lights. Synergy's Stage One treatment invokes the traction-control at about the same point as the regular car, and there's no detectable increase in duration or frequency. In fact, once you get past the initial band of wheelspinning Z06 torque, the car screams right through the rev band with every last horse in there charging. While not quite an apples-to-apples comparison—a bit of Hollenback's added boost was being absorbed by the mass of an extra passenger, namely the grinning Jeff Huston—Synergy's mill feels on par with the stock LS7 down low and noticeably torquier from 3000 revs onward. From that point to redline it pulls forward harder and revs more enthusiastically, particularly in the sweet zone between 4000-6500. In twisty stuff, the pull out of corners using the midrange is so smooth and powerful that it's hard to tell where the car makes the big break from stock and begins adding its extra juice. All you really know is that it keeps reaching the next upshift faster than even the lightning-quick stock version. Thanks to the headers, the sound under full throttle is stronger as well, the LS7 now growling out a deeper note that's especially resonant when the exhaust secondaries open up and the airplane-like swoosh drops a full octave.

I'm sure there are moral implications to making the wickedly fast Z06 even faster, but that's a whole separate subject. The fact that there's still something left to get from these cars will invariably lead tuning fans down that path. Until the new Z06 reaches tire-smoking undrivablity (and probably well beyond), Corvette tuners will keep finding room for improvement no matter how good the starting place is. In fact, by the time you read this, even the conservative and thoughtful team of Hollenback and Huston will have their much more aggressive Stage Two pieces inside this same prototype.

"It's definitely going to be a step up from Stage One," Hollenback says. "[With Stage Two], people are going to see the numbers and say I like that power level." Well, fine: If this chassis can keep putting it down, as Stage One implies that it will, more power to 'em.

Behind the scenes, Jay works the camera.